2nd International Combined Caucus Juried Exhibition:

Women's, Multicultural, and The Lesbian, Gay, Bisexual, Transgender, and Queer (LGBTQ) Caucuses

Catherine Lord: Tender Buttons

Catherine Lord, an artist and writer, divides her time between Manhattan and Hudson, N.Y. Professor Emerita of Art at the University of California, Irvine, she has lately been teaching at Harvard University and Bard College. She is the author of The Summer of Her Baldness: A Cancer Improvisation and (with Richard Meyer) Art and Queer Culture.

Lists.(1) I worship them, they slip from my hands, they stall the narrative, queer is my top, the one I love most, an index of improbable alliances and beautiful friendships, a cascade of doodles, a concatenation of strangers whose affinities split gender open. Consider, for example, this list, courtesy of Sharon Hayes and her open call for performers back in 2008: “lesbians, gay men, bisexuals, transmen, transwomen, queers, fags, dykes, muff divers, bull daggers, queens, drama queens, flaming queens, trannies, fairies, gym boys, boxing boys, boxing girls, pitchers, catchers, butches, bois, FtoMs, MtoFs, old maids, Miss Kittens, Dear Johns, inverts, perverts, girlfriends, drag kings, prom queens, happy people, [and] alien sexualities.” Who wouldn’t go to such a bar? Who wouldn’t prolong the pleasure? Carpet munchers, chapstick lesbians, four-year lesbians, pussies, bears, daddy’s boys, girls next door, horsewomen, snow queens, dinge queens….. This inflects that, that intersects this, and without saying so directly, this is my feeling, feminism finds domicile in the queendom of queer. Queer is generous. Queer is the place to look for the missing future. And maybe, if you stop to think about it, the past. But then old doesn’t show up the queer lists. Old is strange. Old scares people shitless. Old is awkward. Old is off limits. Not that I am to my knowledge near the end of my run, and not to brag, or whine, but old may be freakier than anything else on the queer menu.

Old is the new queer.

Nice bumper sticker, that one.

I’m honored to be here at the invitation of the caucuses, and OF the Society for Photographic Education. I’m especially honored to be here at the instigation of ALL the caucuses. I was involved with SPE for ten important years of my life, from the early 1980s to the early 1990s. Then I got fed up, so for the next 25 years I wasn’t involved at all. I have no knowledge, then, of the twists and turns that brought me here, but I hope I can do justice to whatever it was imagined I might contribute.

In my observation, caucuses are the toughest, rowdiest, most overworked and most energized part of any organization. They are the margins that trouble the center, the margins that move impossibly ponderous battleships in one direction or another, just as muscle, or so yoga teachers tell us, moves bone. Caucuses are a haven for polemicists, cranks, colored folk, dissidents, troublemakers, malcontents and people who remind other people of their promises. In short, caucuses are like an excellent queer bar, and there is no utopia more inclusive, more pragmatic and more politically strategic than a queer bar.

Caucuses are not for slackers. Caucuses want more out of institutions than institutions are prepared to give. If abstractions have feet, caucuses hold their toes to the fire. Caucuses exist because institutions move at a glacial pace and because institutions tend to be smug about the very existence of their own blind spots. Caucuses not only cause expensive operating systems to crash, they force them to reboot.

My aim is not so much to rewrite history as to incite the past in order to call into being my imaginary: the transubstantiation of dreamers that I hope might be sitting out there in the audience. I want to invent—and invention does not equal fiction-- a connection between what it was in my thirties to be involved with the women’s caucus of SPE, and what I hope might now be the case, as I stand here, in my sixties, a lesbian and a feminist and a queer, a Dominican and a dyke, all too well aware of the chasms between those terms. I’m interested in drag, deployed with the sort of rueful irony that includes engineering objects that could one day fly, but probably won’t, as well as the more fabulous decodings of costume and gender. I intend drag in the sense that Elizabeth Freeman defines it, “a productive obstacle to progress, a usefully distorting pull backward, and a necessary pressure on the present tense.” (2)

My aim is not so much to rewrite history as to incite the past in order to call into being my imaginary: the transubstantiation of dreamers that I hope might be sitting out there in the audience. I want to invent—and invention does not equal fiction-- a connection between what it was in my thirties to be involved with the women’s caucus of SPE, and what I hope might now be the case, as I stand here, in my sixties, a lesbian and a feminist and a queer, a Dominican and a dyke, all too well aware of the chasms between those terms. I’m interested in drag, deployed with the sort of rueful irony that includes engineering objects that could one day fly, but probably won’t, as well as the more fabulous decodings of costume and gender. I intend drag in the sense that Elizabeth Freeman defines it, “a productive obstacle to progress, a usefully distorting pull backward, and a necessary pressure on the present tense.” (2)

One way or another, this event is about education, which means talking about performance, resistance, willful ignorance, and the complex interchange between generations. Education is not a one-way thing. It’s not just what I might say to you, but what you have said and might say to me.

“Queerness is not yet here. Queerness is an ideality.” So wrote the late Jose Munoz, lighting yet another fire on the subject of queer as ethic and as ethos. “Put another way” he continues, “we are not yet queer. We may never touch queerness, but we can feel it as the warm illumination of a horizon imbued with potentiality. We have never been queer, yet queerness exists for us as an ideality that can be distilled from the past and used to imagine a future. Queerness is a structuring and educated mode of desiring that allows us to see and feel beyond the quagmire of the present.” (3)

“Queerness is not yet here. Queerness is an ideality.” So wrote the late Jose Munoz, lighting yet another fire on the subject of queer as ethic and as ethos. “Put another way” he continues, “we are not yet queer. We may never touch queerness, but we can feel it as the warm illumination of a horizon imbued with potentiality. We have never been queer, yet queerness exists for us as an ideality that can be distilled from the past and used to imagine a future. Queerness is a structuring and educated mode of desiring that allows us to see and feel beyond the quagmire of the present.” (3)

News flash. Disclaimer. Lest ladling on the queer theory be causing anxiety, far be it from me to imply that every member of every caucus or of the Society for Photographic Education is or should or can or could be somehow queer, or to assume that every one of those people would take the word in the spirit in which it is intended--as a compliment.

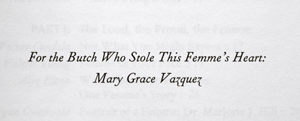

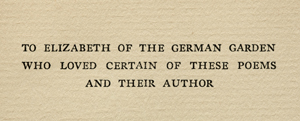

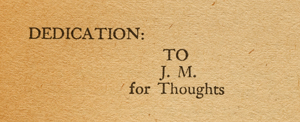

By speaking as if there were an audience, the book dedication invents its audience, a kind of spatial subjunctive, a virtual address where the reader takes a seat in the audience merely by learning that such an audience might exist. Naming a recipient, or recipients, invites the reader into a location where she can find the possibility, or the choice, or the necessity, or the structuring fantasy, of being addressed. What is given by writing, in writing, provokes into being an audience larger than the nominal recipient. Strangers are recruited to a social imaginary. The idea of a recipient creates a community that constitutes itself by imagining the act of reception. Hyperbole equals utopia. The future pulls the past into the present. The insistence on the small detail, the unindexed, the irretrievable, rewrites the past and maps a more capacious future.

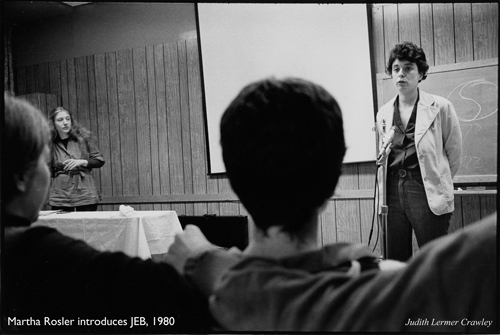

This is what it looked like when feminism encountered photography at the SPE National Conference in 1980, thirty-four years ago. We’re in Swan Lake, New York, a Borscht Belt resort even then on its last legs and no doubt a bargain for an organization struggling to professionalize itself without benefit of a budget. At the center of the photograph is a white infant. To the photographer the fact of motherhood was the most important part of the occasion—that, and framing the photograph to suggest that chairs had been placed in a feminist consciousness raising circle. Everyone would have her chance to speak. Everyone could finish without interruption. Everyone was equal. Etcetera. Not a bad legacy from the 1970s, and a legacy that continues in many art school classes, innocent of its origins in supposed essentialism or in goddess worship. Was the child the photographer’s? I think not, but I admit at the time I probably wished that Judith Crawley was paying attention to what was being said, rather than fiddling about to frame an infant front and center so that she could put motherhood and reproduction, and therefore heterosexuality, right in the middle of feminism.

This is what it looked like when feminism encountered photography at the SPE National Conference in 1980, thirty-four years ago. We’re in Swan Lake, New York, a Borscht Belt resort even then on its last legs and no doubt a bargain for an organization struggling to professionalize itself without benefit of a budget. At the center of the photograph is a white infant. To the photographer the fact of motherhood was the most important part of the occasion—that, and framing the photograph to suggest that chairs had been placed in a feminist consciousness raising circle. Everyone would have her chance to speak. Everyone could finish without interruption. Everyone was equal. Etcetera. Not a bad legacy from the 1970s, and a legacy that continues in many art school classes, innocent of its origins in supposed essentialism or in goddess worship. Was the child the photographer’s? I think not, but I admit at the time I probably wished that Judith Crawley was paying attention to what was being said, rather than fiddling about to frame an infant front and center so that she could put motherhood and reproduction, and therefore heterosexuality, right in the middle of feminism.

Those were the thoughts of an arrogant young lesbian who, for once, did not blurt out exactly what she was thinking. In retrospect, I’m grateful that Judith took this photograph and hope that the infant has, these 35 years later, survived to earn at least one advanced degree, or gotten stinking rich off a tech start up, or is happily married to his husband while helping to support his mother. Or maybe she is in the midst of sex reassignment surgery. Or gone

vegan. Or dead. Or sitting in this audience. Judith and I haven’t had a real catch up. One drifts apart. One loses touch. One has no gossip and one therefore devolves to the tedium of the pronoun “one.” Nonetheless, in 1980, in Swan Lake, I promise you that dissatisfaction was in the air and giddy energy was spilling over. It was a feminist moment. Carolee Schneemann, for example, had performed Interior Scroll five years before, Heresies had just put out its lesbian issue, and

Martha Rosler had made The Bowery in Two Inadequate Descriptive Systems. The feminist list could be extended, of course, but most important for my purposes here, Martha had gathered together for Swan Lake a superlatively lefty panel that gave many of us, gasping for air in the heavy atmosphere of fine art photography, the lightness we needed to breathe.

I know the panel to have been a pivotal intellectual event even though the only participant I can actually remember is Joan Biren, the fetching baby dyke being introduced by Rosler. Biren, who went by the moniker JEB, was way further out of the closet than I believed myself to be at the time, and thus in my memory she remains inflated to a much taller, more muscly, more butchly presence than this photograph says she was. Martha and JEB and other couple of other artists I don’t remember for the embarrassingly obvious libidinal reasons provided the oxygen to fan the flames. Martha was a few years older and vastly more cosmopolitan than my crowd--the grad students who had squished into someone’s wreck of a car to drive to Swan Lake from Rochester, NY. She dispensed advice, I imagine, as she often does, including the information that College Art already had something called a Women’s Caucus and that by making waves it was getting money to do the sort of things we wanted to do.

I know the panel to have been a pivotal intellectual event even though the only participant I can actually remember is Joan Biren, the fetching baby dyke being introduced by Rosler. Biren, who went by the moniker JEB, was way further out of the closet than I believed myself to be at the time, and thus in my memory she remains inflated to a much taller, more muscly, more butchly presence than this photograph says she was. Martha and JEB and other couple of other artists I don’t remember for the embarrassingly obvious libidinal reasons provided the oxygen to fan the flames. Martha was a few years older and vastly more cosmopolitan than my crowd--the grad students who had squished into someone’s wreck of a car to drive to Swan Lake from Rochester, NY. She dispensed advice, I imagine, as she often does, including the information that College Art already had something called a Women’s Caucus and that by making waves it was getting money to do the sort of things we wanted to do.

To cause a fluid to bleed upon the unmarked skin of a page is to assume a position in a matrix of generosity. When a reader reads the dedication of a book she holds in her hand, she necessarily realizes that the object for which she, or someone, paid good money is not, properly speaking hers. She is invited into the sphere of other people’s intimacy, be that hope or love or bitterness. She benefits without the obligation to possess. Indeed, she learns because she cannot possess. By holding someone else’s property, she absorbs the erotic charge of the intellect.

To cause a fluid to bleed upon the unmarked skin of a page is to assume a position in a matrix of generosity. When a reader reads the dedication of a book she holds in her hand, she necessarily realizes that the object for which she, or someone, paid good money is not, properly speaking hers. She is invited into the sphere of other people’s intimacy, be that hope or love or bitterness. She benefits without the obligation to possess. Indeed, she learns because she cannot possess. By holding someone else’s property, she absorbs the erotic charge of the intellect.

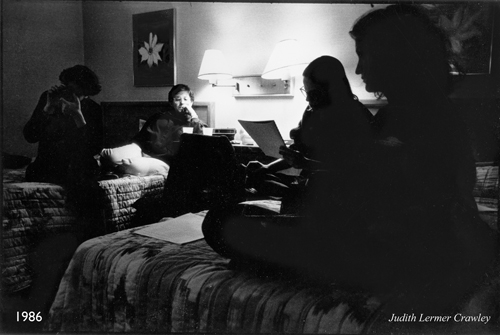

Before the conference ended, we gathered in someone’s room to discuss our options. Doubtless the room was shared by 15 people, and doubtless someone stole the towels and bedding to take home because we were broke and needed such things in our apartments. Somehow or other, it seemed not only possible but necessary and right to crack SPE open, to make an organization supported by the dues of its members something more than a boy’s club led by white men with ponytails and, more often than not, cowboy boots. Even after some of them outgrew the pony tails and boots, because not every man can carry off such an outfit in perpetuity, it was a denim, cigarettes and whiskey crowd. In other words, the SPE leadership was an artifact of a particular aspect of the 1960s even though one of the boys was, I think, gay. That he was deeply closeted is another artifact of the 1960s.

Before the conference ended, we gathered in someone’s room to discuss our options. Doubtless the room was shared by 15 people, and doubtless someone stole the towels and bedding to take home because we were broke and needed such things in our apartments. Somehow or other, it seemed not only possible but necessary and right to crack SPE open, to make an organization supported by the dues of its members something more than a boy’s club led by white men with ponytails and, more often than not, cowboy boots. Even after some of them outgrew the pony tails and boots, because not every man can carry off such an outfit in perpetuity, it was a denim, cigarettes and whiskey crowd. In other words, the SPE leadership was an artifact of a particular aspect of the 1960s even though one of the boys was, I think, gay. That he was deeply closeted is another artifact of the 1960s.

The boys—and I mean that literally, as they were all what we would now call bioboys, a term which I use with equal amounts of irony and affection--had founded SPE in 1963 to promote themselves and their work within academic institutions. They were not, in fact, well treated by the academy or by the gallery and museum world. But despite the fact that the image culture of the twentieth century was the camera image, the bioboys had strategized themselves into professionalism through the route of fine art photography, and thus few people in 1980 could afford to admit postmodernism or appropriation to their discipline. Photography hadn’t really, for example, absorbed the effects of two major events of 1977: Susan Sontag’s legendary collection of essays and Douglas Crimp’s “Pictures” exhibition.

The book dedication tenders the gifts of labor and love. A token of affection, a mark of esteem, a sacrifice of one’s time, dedication carries the connotation of binding oneself to a cause, to a tradition, or to another person. Dedications can be considered or proffered at the last minute, decided late at night or first thing in the morning, offered in homage, in thanks, in love, in repayment of a debt, in caprice, even in revenge. To dedicate a book is to place upon the page a sentiment that is almost never indexed. You must be looking to find a book dedication. Either you touch what used to be a forest or you rely on the kindness of friends and the benevolence of librarians, who notice these things. A dedication is a speech act. Just as saying the words, “I do thee wed,” cause to come into being a marriage, to put into print, inside a book, the words “I make you a gift of the words I have written,” is to cause the statement to be true, to tender to another, in advance, the very object that the reader holds in her hands. It is to make a gift upon the material that gives the gift its existence. To compose the type that allows ink to bite paper is to join a community working to make a culture tangible. To say it is to do it. If in truth most books and works of art are made with one or two (maybe five) people in mind, their staying power is a function not of numbers but of a chain of recipients who understand a gift as something other than an invitation to barter, those who will forward the gift, who will keep it in motion rather than being consumed by it.

The book dedication tenders the gifts of labor and love. A token of affection, a mark of esteem, a sacrifice of one’s time, dedication carries the connotation of binding oneself to a cause, to a tradition, or to another person. Dedications can be considered or proffered at the last minute, decided late at night or first thing in the morning, offered in homage, in thanks, in love, in repayment of a debt, in caprice, even in revenge. To dedicate a book is to place upon the page a sentiment that is almost never indexed. You must be looking to find a book dedication. Either you touch what used to be a forest or you rely on the kindness of friends and the benevolence of librarians, who notice these things. A dedication is a speech act. Just as saying the words, “I do thee wed,” cause to come into being a marriage, to put into print, inside a book, the words “I make you a gift of the words I have written,” is to cause the statement to be true, to tender to another, in advance, the very object that the reader holds in her hands. It is to make a gift upon the material that gives the gift its existence. To compose the type that allows ink to bite paper is to join a community working to make a culture tangible. To say it is to do it. If in truth most books and works of art are made with one or two (maybe five) people in mind, their staying power is a function not of numbers but of a chain of recipients who understand a gift as something other than an invitation to barter, those who will forward the gift, who will keep it in motion rather than being consumed by it.

In the early 1980s, then, photography was viewed as one of the minor arts, a subset of a subset of printmaking. And here we were, the biogirls—a term I use because we were barely dealing with sexuality, or gender as a plural and as a construction, or even, in those same terms, race and class—here we were, telling the bioboys to move over because they bored us. It wasn’t even twenty years after they founded their organization. Chutzpah. Balls. Other adjectives were doubtless applied. Rude. Whatever. We were already the majority of students in MFA programs and we wanted a slice of the pie. We wanted programming that we found compelling because we wanted to learn and to teach things that were new to us. In that cause we incited, or by our own failings provoked, other troublemakers: lefties, queers, students, and people of color.

We wanted, back in the day, more out of photography than the generation of photographers who preceded us was prepared to hand over. We could have been had for a reliable 20% of the budget, but instead, we had to fight for anything we got, and the fights, as fights tend to be, were clumsy. People flailed. The blows left bruises. S & M was not yet chic, or not in SPE, so it would have been difficult then to turn the bruises into a teachable moment. There were petitions and proposals, lots of them, not to mention sheaves of pretentious letters, typed on typewriters which we must have actually lugged to the various conferences, long before the days of suitcases with wheels.

We wanted, back in the day, more out of photography than the generation of photographers who preceded us was prepared to hand over. We could have been had for a reliable 20% of the budget, but instead, we had to fight for anything we got, and the fights, as fights tend to be, were clumsy. People flailed. The blows left bruises. S & M was not yet chic, or not in SPE, so it would have been difficult then to turn the bruises into a teachable moment. There were petitions and proposals, lots of them, not to mention sheaves of pretentious letters, typed on typewriters which we must have actually lugged to the various conferences, long before the days of suitcases with wheels.

We submitted, for example, seven panel proposals for the 1986 conference, which was held right here in Baltimore. All but one panel was rejected on the grounds that our proposals didn’t address photography and photographic education. (That part of the rejection letter was decisively underlined.) In other words, though the conference theme that year was “Stand in a Different Place,” artists such as Mary Kelly, Jo Spence and Suzanne Lacy were told either that they didn’t make the grade or that their work had nothing to do with photography and education. The place in which they stood was apparently not just different but a planet with infested with dangerous life forms. Which was, in many ways, true. That’s why I’m standing here today, why the work of the artists I’ve named is important and why, in hindsight, to have rejected them seems at the very least a shortsighted move. But then exclusion is inevitably and still achieved in the name of quality or procedure, or both.

The story I am telling you involves various conundrums of reading and writing. It doesn’t go in a straight line and it is fissured by tensions between activism and solitude. I have the habit of books.

I read footnotes. I read the footnotes in books on footnotes. I own books on footnotes. I photograph ledgers that record library fines. I believe it a crime to jettison card catalogs. I record errata slips, epigraphs, the manner of other people’s note taking—marginalia, question marks and exclamation marks. Librarians could be my sexual orientation, or preference, whichever, whatever, it doesn’t matter much, the debate is an expense of spirit and a waste of time. “What if the most gratifying reading,” asks Moyra Davey, “is the one that also entails the risk of producing a text of one’s own?” (4) The unruly shimmers of emotion that fuel cultural resistance—evanescent flickers of rage and desire and humiliation--continue to manifest in unexpected places, disrupting narratives that are not theirs, reminding us that chronology is a formal constraint and a creative disturbance.

“Female reality,” wrote Eileen Myles a few years ago, eviscerating the scant coverage of writing by women in publications such as the New York Review of Books, “female reality (and this goes for all the

“other” realities as well—queer, black, trans—everyone else) is more interesting because it is wider, more representative of humanity—it’s definitely more stylistically various because of all it has to carry and show. After all, style is practical. You do different things because you are different.” (5)

“Female reality,” wrote Eileen Myles a few years ago, eviscerating the scant coverage of writing by women in publications such as the New York Review of Books, “female reality (and this goes for all the

“other” realities as well—queer, black, trans—everyone else) is more interesting because it is wider, more representative of humanity—it’s definitely more stylistically various because of all it has to carry and show. After all, style is practical. You do different things because you are different.” (5)

OCCUPY photography. That was the idea.

Occupy the whole damn thing. We were engaged in institutional critique before that phrase became a career or an exhibition or an anthology or a job. Because we didn’t know any better, we managed amazing things—among them a special issue of Exposure and a survey of women and people of color in higher education, also published in Exposure. We raised the money to bring in our own speakers, from the U.S. and abroad, and we organized at least one entire conference, “Media Women,” held at Hunter College in 1986. For me, during those first ten years, the Women’s Caucus was formative, and I know that it shaped or profoundly affected other women—among them Deborah Bright, Connie Wolf, Joann Seador, Martha Gever, Diane Neumaier, Sally Stein, Aneta Sperber, Judith Crawley, Nancy Floyd, Linn Underhill, Carrie Mae Weems, Abigail Solomon Godeau, Joyan Saunders, Linda Brooks, Jan Zita Grover, Kaucyila Brooke, Nathalie Magnan. I know that it changed men like Douglas Crimp, Allan Sekula, and David Trend.

I can list the people to whom I remain grateful, but I can’t put names to most of the women in any particular one of Judith Crawley’s images. A photograph is not a memory. Cameras cannot inventory the surplus affect that unites collectives, divides their members, delays change and pushes it to the surface down the road. That I can lay my hands on the desire to name and to categorize does not mean that I can retrieve from a photograph those named or categorized. Nonetheless, let us acknowledge that these groups solidified and dissolved because of particular, predictable, inevitable personal stories that not only generated the passion for political action but also made it more compelling erratic and irrational. To paraphrase Doug Huebler, I could say of this photograph, for example, at least one person represented above went crazy, at least one person represented above had an abortion, at least one person represented above got tenure, at least one person represented above should have known better, at least one person represented above had a solo show, at least one person represented above is a homophobe, at least one person represented above had cancer, at least one person represented above became the director of a major museum, at least one person represented above needs a makeover.

One moment in particular sticks. It was in Minneapolis, and therefore it was in 1985. The women’s caucus had decided that though our programming was obviously public, our organizing meetings were for women. A guy whose name was Derek or Daniel, or Donald, or perhaps a name that didn’t in fact begin with D, but who had a tendency to come to the women’s caucus meetings because he had much to contribute, Derek went to the board and protested our reverse discrimination. The chairwoman of the SPE board, solemnly invoking federal funding by the National Endowment for the Arts, decided to allow David or Derek or Donald to penetrate our meeting by the simple expedient of having hotel staff remove the temporary walls that gave our discussions privacy and humor and irony. Let us call the resulting performance Wall Removal by Hotel Maintenance Staff, Working Overtime. I remember, perhaps incorrectly, that hotel workers were also asked to remove the chairs from under our reverse discriminatory butts. We continued to discuss programming and planning, and David or Derek or Donald, having gotten what he wanted, or they wanted, if he was in fact, more of a collective noun than a singular, sat quietly to one side, absorbing the spectacle that we had no choice but to enact.(6) It was muddle of emotions: we were foolish, we were naïve, we were loud, we were glorious, we were the victors, we were the vanquished, we were obnoxious, we were brave, we were earnest, we were naked, we

we were so young that it didn’t bother us to have to sit on the floor.

One moment in particular sticks. It was in Minneapolis, and therefore it was in 1985. The women’s caucus had decided that though our programming was obviously public, our organizing meetings were for women. A guy whose name was Derek or Daniel, or Donald, or perhaps a name that didn’t in fact begin with D, but who had a tendency to come to the women’s caucus meetings because he had much to contribute, Derek went to the board and protested our reverse discrimination. The chairwoman of the SPE board, solemnly invoking federal funding by the National Endowment for the Arts, decided to allow David or Derek or Donald to penetrate our meeting by the simple expedient of having hotel staff remove the temporary walls that gave our discussions privacy and humor and irony. Let us call the resulting performance Wall Removal by Hotel Maintenance Staff, Working Overtime. I remember, perhaps incorrectly, that hotel workers were also asked to remove the chairs from under our reverse discriminatory butts. We continued to discuss programming and planning, and David or Derek or Donald, having gotten what he wanted, or they wanted, if he was in fact, more of a collective noun than a singular, sat quietly to one side, absorbing the spectacle that we had no choice but to enact.(6) It was muddle of emotions: we were foolish, we were naïve, we were loud, we were glorious, we were the victors, we were the vanquished, we were obnoxious, we were brave, we were earnest, we were naked, we

we were so young that it didn’t bother us to have to sit on the floor.

I haven’t found a photograph of this event. Judith Crawley wasn’t there. Even if I could show you a photograph, it would lie, because that is what photographs do. This is a story of back and forths, call and response. Nothing in the story proceeds in a straight line. There are forgettings, erasures, emendations, switchbacks, gaps, strategic reinventions, acid criticisms, entirely justified, but most of all humor, a leaning to failure, and a bodily obsession with reperformance that understands there is actually no original.

The act of dedication occupies that uncharted time and uncertain space between thoughts disciplined into words and the binding of those thoughts upon paper. The gift does not exist, and thus cannot be made, until the object is brought into existence by a spine. The gift is perverse. The giver does not relinquish what she has given. Even if she wished to do so, she could not. Rather, the gift binds its giver to the recipient. And whether or not the recipient wished the gift, she is forever bound to the giver.

Notes:

1. The following is an edited version of a talk delivered at the Society for Education National Conference, Baltimore, MD, March 7, 2014. All black and white photographs are courtesy of Judith Lerner Crawley. All photographs of book dedications are details from Catherine Lord, “To Whom It May Concern,” installation of 175 ink jet prints, each 23 in. x 9 in., 2011. My thanks to the ONE Archive, Los Angeles, the various caucuses of the Society for Photographic Education, now and back when, as well as Linda Brooks and Judith Lerner Crawley.

2. Elizabeth Freeman, Time Binds: Queer Temporalities, Queer Histories (Duke University Press, 2010), p. 64.

Jose Munoz, Cruising Utopia: The Then and There of Queer Futurity (New York: NYU Press, 2009), p. 1.

3. Jose Munoz, Cruising Utopia: The Then and There of Queer Futurity (New York: NYU Press, 2009), p. 1.

4. Moyra Davey, The Problem of Reading (New York: A Documents Book, 2003), p. 38

5. Eileen Myles, “Being Female,” The Awl, Feb. 14, 2011.

6. As it turned out, the NEA didn’t actually have a problem: the meeting was about organizing programming, an activity which didn’t have to be public, as opposed the programming itself, which obviously, and properly, had to be public. Nobody could split that particular procedural hair, however, until the conference was over. We were de-walled on a Saturday; nobody, especially in the days of land lines, could be expected to answer the phone in Washington on a Saturday.

* The editors wish to thamk Catherine Lord for permission to publish her 2014 SPE presentation in total.