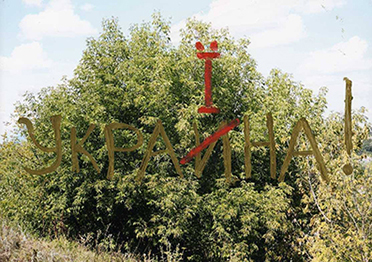

Kharkiv School of Photography: Soviet Censorship to New Aesthetics:

Part 3 - Contemporary Photographers Exhibition 2

Kharkiv Photography in Independent Ukraine. Vita heroica vs. Vita minima

Tatiana Pavlova, Ph.D.

This is the third essay of the exhibition series “Kharkiv School of Photography” by Tatiana Pavlova. The Kharkiv School of Photography is not a physical school but a collective of photographers who began working together in the 1970s and continue in different formats until today.

Tatiana Pavlova.1980 – Faculty of Art History at National Academia of Fine Art and Architecture, Kiev. Ph.D. Docent of Art History chair in Kharkiv State Academy of Art and Design. Curated art exhibitions since 1988 in Ukraine, Russia, Slovakia, Germany, USA. Author of essays on Photography of Ukraine in the History of European photography in the 20th century. Author of books and articles about Ukrainian art and photography. Lectured on Ukrainian photography in Kharkiv, Kiev, Moscow, Bratislava, Poprad, Warsaw, New York.

The breakdown of the Soviet Union and Ukraine's becoming an independent state in 1991 brought out the question of the authenticity of Ukrainian culture. From the very beginning, the Kharkiv photography underground displayed features of its own style. In 1993, at the First International Symposium on Contemporary Arts (Evolution of Contemporary Arts in Ukraine) organized by the Soros Center for Contemporary Art in Kiev, I formulated these features as dramatization, aestheticism and hedonism, paradoxically combined with brutality.

The middle of the 1990s was marked by substantial re-grouping of the artistic activity in Ukrainian photography. After the closure of the “Panorama” (see Essay 2) Sergei Bratkov’s private “Up-Down” gallery took on initiative. This small space became the place to show different conceptual projects, primarily of the the ‘Group of Immediate Reaction’ (or Rapid Response Group; it included the artists Sergei Bratkov, Boris Mikhailov, and Sergei Solonsky).

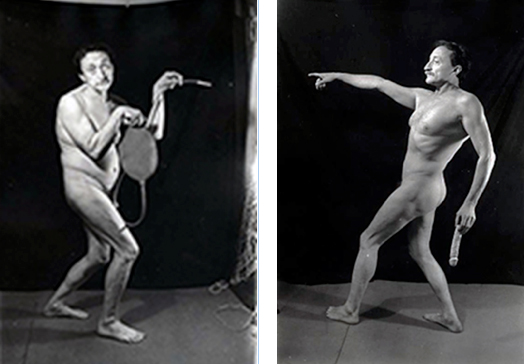

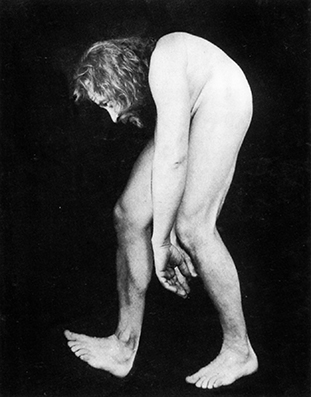

© Boris Mikhailov. I am not I. 1992

It was in the “Up-Down” gallery that Boris Mikhailov’s scandalous I am not I project (1992) was shown for the first time. The first exhibition of this work mixed ritual and magic with a shade of blasphemy. Entrance to the show demanded involuntary participation in the profanation of the author’s body by stepping over it on the dark stairway. This stairway, then, led into the exhibition space requiring one to participate further in his rehabilitation--the raising and canonization which took place in an interior similar to a Christian chapel being the second part of the action (family gallery as interpreted by the author). Traditional icons in the exhibition’s opening were replaced by the images of the author, represented naked in erotic hieratic and other poses with various props, among which a dildo was allotted a special meaning. Double fetishization of the image of the “saint“ body and the opposite as the superman’s body (through the number of poses and super-attributes) had their semiotic conflict as the main objective.

The museum version of the exhibition (1994) brought up another conflict: this time between the language of the museum and the kitsch of pornography which caused a scandalous closing of the show (see a video interview with Valentina Myzgina, Kharkiv Fine Art Museum Director, in Exhibition 2).

Тhis well-known work may be interpreted as a statement about the body, by the body itself, that can be compared to plastic expression of the deaf-mute language. A spectator is forced to defend against the eccentric simplicity and “mindlessness” of the images by looking for their prototypes in photography and classic art. Though this work sums up Mikhailov’s ironic games with porno-photo and attributes of phallocracy by compromising them, the main focus of his work is concentrated on exposing the most important taboo. Mikhailov named it “the last taboo” that was not abolished by democracy.

The Group of Immediate Reaction played a special role in the maturing of Kharkiv photography. It hammered the last nail into the coffin of the utopian dream of Kharkiv Unity. (From 1993 to 1997, there were 22 exhibitions held in the Up-Down gallery, most of them quite provocative in nature. It was also this gallery that housed some of Bratkov’s individual projects, such as Chikatilo’s Diary, No Heaven, 1995.)

The Group of Immediate Reaction played a special role in the maturing of Kharkiv photography. It hammered the last nail into the coffin of the utopian dream of Kharkiv Unity. (From 1993 to 1997, there were 22 exhibitions held in the Up-Down gallery, most of them quite provocative in nature. It was also this gallery that housed some of Bratkov’s individual projects, such as Chikatilo’s Diary, No Heaven, 1995.)

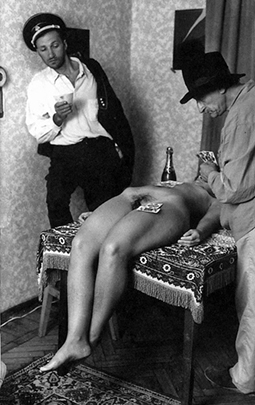

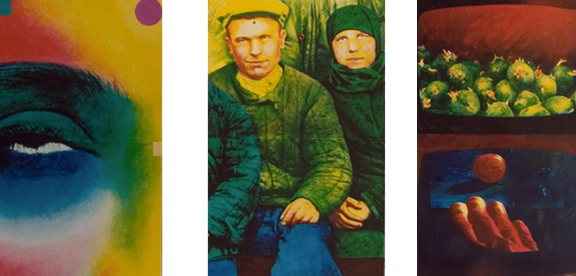

(Image left: © TheGTroup of Immediate Reaction. If I Were German.1994)

The group’s most famous works include Spitting on Moscow (1994) held in the Kharkiv Zoo, A Box for Three Letters, A Sacrifice to the God of War, and of course, If I Were German (1994). This controversial piece by Mikhailov, Solonsky, Bratkov (and Vita Mikhailova), was widely successful.

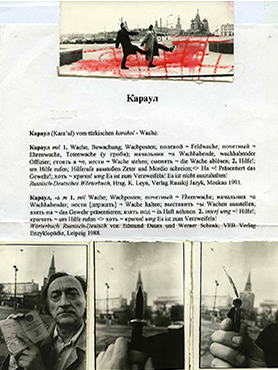

Among the group’s last projects was The Guard (1995), the result of a disappointing visit to Moscow’s Red Square in. When Mikhailov, Mikhailova, and Bratkov marched across this sacred spot, the local police saw it as a demarche. It is not surprising that their first (Spitting on Moscow) and last (The Guard) performances revolved around Moscow, indicative of the efforts to gain independence, to distance themselves from the Moscow-centered approach, which was symptomatic of Ukrainian art of the 1990s.

(Image right: © The Group of Immediate Reaction.The Guard.1995)

© Sergey Bratkov. Army girls. 2000

Even within these collective projects, Bratkov was clearly developing his own style, showing a keen interest in narrative interpretations. This led to a number of individual projects done in the late 1990s, mostly in Moscow in collaboration with the "Regina" gallery (curator V. Оvchareko). These were mostly kitsch-style serial portraits, such as The Children, Spetsnaz, Future Pilots, Second Hand (all 2000), Khokhlushki (2001), Moryachki (Sea-women, 2004). In 2003 Bratkov participated in the Venice Biennale representing Russia.

© Eugeny Pavlov. Totalnaja Fotografia Series.1992

Kharkiv photography’s integration into the fine art paradigm in the 1990s was also evident in its dialogue with other art mediums. In 1994, Eugeny Pavlov showed the Totalnaya Fotografia (Total Photography) project as a product of this  interartscape1, and later he continued this action-painting-experiment in photography through collaboration with the artist Vladimir Shaposhnikov, who joined him in 1996.

interartscape1, and later he continued this action-painting-experiment in photography through collaboration with the artist Vladimir Shaposhnikov, who joined him in 1996.

Pavlov’s Total Photography project used his archive of the Soviet period photographs. It was exhibited in the USA. In the multi-layered photographs, William Zimmer (The New York Times) saw resemblance to Ancient icons, with “their gold backgrounds and frozen expressions on the faces”2.

However, the roots of this archaic impression resided elsewhere. Using Soviet-made materials meant inevitable defects (accidental scratches, dust and other artifacts) in which Pavlov envisioned some metaphysical information that had to be manually highlighted and emphasized. Another technique of this metaphysical "development" of photographs came to be "a brakeless gesture," easily readable in the color lines and stains laid on the pictures. The destruction of the photographic image was redeemed by the extensive opportunities it offered. (The above image: © E.Pavlov and V.Shaposhnikov. The Common Field.1996)

The project grew and required considerable efforts in order to overcome barriers between photography and painting, and this was when Vladimir Shaposhnikov came up with an idea, and a collaborative project termed The Common Field (1996) appeared (curator T.Pavlova). Both artists, in turn, applied color to black-and-white photographs from Pavlov’s archive. "The third author," said the artists, "is the place where we find ourselves beyond mutual boundaries.” 3

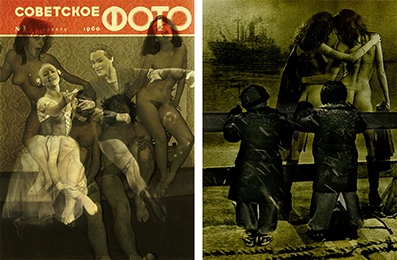

© E.Pavlov and V.Shaposhnikov. Parnography. 1998

© E.Pavlov and V.Shaposhnikov. Parnography. 1998

It had an unusual sequel in the subsequent Parnography project by Pavlov and Shaposhnikov. Its inclination towards utopism determined not solely the continued interactive approach, but also the special topic. Paired photographic portrayals were here examined in their relation to erotic photography (the project title utilizes a “pair – porno” pun in Russian and Ukrainian). The altered code of sexuality became apparent in an intentional connection of photographs from the 1990s with their hypodynamic plasticity, and a tense expression of the polygonal, pansexual 1970s. The onset of eroticism in post-Soviet society ushered in a deluge of new problems: for instance, those due to the shift of erotic photography from a peripheral commercial genre (a mode in which it had existed since the origins of the photographic process) to a central one.

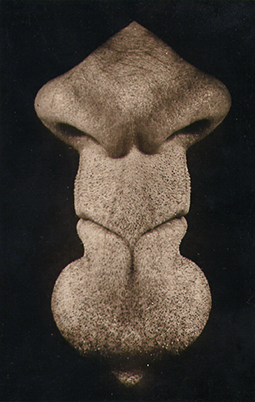

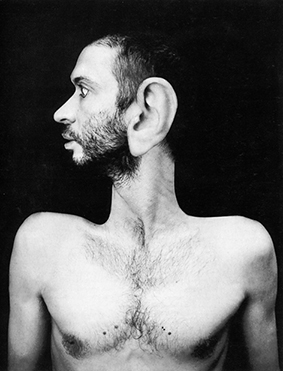

©.Sergey Solonsky. Selfportrait. 1990s

“Bodily transformations” are of particular interest in the work of Sergey Solonsky. Corporeal fragmentations in his pictures, from the turn of the 1980–90s, started the aesthetic revolution in Ukrainian photography. The accent on corporeality and a new wave of expressionism provided energy for the final split with surrealistic fancy, characteristic for the period of the Vremya group. In his “anthropocreation” photomontages he started with anatomical research, dissecting the ideal á la Leonardo da Vinci. In the middle of the 1990s he made a series of module collages, which manifested this interest in anatomy as a distinctive artistic feature (compare Jackson Pollock’s pop-name Jack the Dripper – and Jack the Ripper being the prototype). Solonsky’s collages, which represent “fantasy” in the corporeal genre, materialize the rare deliverance from the Self, from various taboos, and universality. This unexpected revenge of phallocracy after Mikhailov’s gesture of dissaproval in “He is not He” (famous Mikhailov’s work was entitled so by D. Newmayer) – its invasion into the sacred sphere of cultural symbols – meant, nevertheless, the paradoxical movement aiming at the naturalization of reality.

©.Sergey Solonsky

Solonsky’s corporeal collages are, in fact, portraits – and more precisely, portrait–dreams. In his collages one body dreams about a big musical ear, another about “the third eye.” The photographer as a constructivist artist analyzes the model and synthesizes it in a new order, making the collages by hand (without the computer, thus anticipating the Photoshop capabilities). These bodies belong to locally “celebrated people,” therefore close-up details are organically used here as a specific way of looking through the lorgnette at a “celebrity.” This “grandma’s looking glass” manner, popular at the turn of the twentieth century, as well as the propensity for working by hand in photography (a characteristic feature for Kharkov school as a whole), give a specific retro-atmosphere to Solonsky’s “alchemy of the body.” Reconstruction of these alchemy elements corresponds to the topic of cultural mutation.

© Sergey Solonsky.1990s.

Representation of the latent smallness of the body interior, its small elements with blood in the first place is a characteristic feature of many actions of Ukrainian photography of the 1990s. “Medical”, “Leonardo’s” and mythological aspects fill in various levels of this interior topic.

The history of accentuating the naked male body in the photos by Pavlov, Rupin, Mikhailov, and Solonsky in the 1970s and 1980s is concluded in the exploration of the secrets of sexes in the works by Mikhailov, Solonsky, Bratkov (and A. Savadov and I. Chichkan in Kyiv) in the 1990s.

© Andrey Avdeyenko and Alexey Yesunin. An Extraterrestrial Diary. 1999

"An Extraterrestrial Diary" (1998) by Andrey Avdeyenko and Alexey Yesunin (Bratislava, 1999) was among specific projections of psychosomatic problems. The conceptual narrative in this work, regardless of the use of classical genre of “the found manuscript“ (the “found” film was developed by Avdeyenko, the “found” diary deciphered by Yesunin) sounded urgent like a medical report.

The syndrome of a contactor with extraterrestrial civilizations, born in the twentieth century, became especially popular after the fall of the Soviet empire which had pretended to be a cosmic empire as well. For the same reasons, in the nineteenth century the “Napoleon complex” became widely spread after Waterloo. It resulted in the body being lost again for natural human functions. In the photographs of this project the eyes glide over the bodies without distinguishing them, they are swarming in the light beam of a spaceship, vanishing in the flickering of the flash. The value of the bodies is reduced to “human waste,” much like the bodily life is substituted for the maniacal dominant in an insane mind.

. 1990s.jpg)

© Igor Chursin. Portrait (Andrey Bogatyriov). 1990s

.Igor Chursin has always made use of photography’s capacity for the absurd. He builds upon a vast cultural foundation, imbuing routine subjects and protagonists with mystic traits, with the trivial picture frame replaced by a mandala. The same approach is evident in his coloring of the photographs.

© Igor Karpenko

Another photographic artist of the absurd, using body acrobatics, Igor Karpenko, burst upon the scene in the mid-1990s. His studio pictures offer the sort of surrealism that has become a mainstay of popular culture, projecting familiarity rather than enigma. The humorous nature of this naive pseudo-surrealism, free of any anxious undertones, made it a viewers’ favorite.

©.Alexander Papakitsa. U/t. 1998

The mysterious distance, in which the body-soul is represented in conceptual projects, for example in The Roof by Alexander Papakitsa (1966-1998), changes the everyday triviality, banal availability in reportage series, representing the human types of the “genre of crisis.” A whole range of thematic portrait series of the 1990s pictured human beings, placed within the limits of survival, or even beyond. Mikhailov’s Case History, Snowdrops by Sergei Bratkov (Frozen Landscapes) fixed the result of observations, confirming peculiar manifestations of a new quality that appeared in man.

© Oleg Malevany. Over the Line

The aesthetic saturation of the well-known Kharkiv artist Oleg Malevany’s photography is also related to flowers, as in his portraits of women (Metamorphoses 1993). It was he who developed the liking for the colour intervention in the photos of the Kharkiv School community. The red scale played an important part in Malevany’s spectrography, which found its principal expression in a number of series where red dominated the rest of the chromatic scale. This experimental approach found its ultimate expression in a series of photographs that transcended the boundaries of red, crossing the line (Behind the Line is the actual series title) into the infrared. As a result, symbolic Kharkiv locations are highlighted by irrational allusions, appealing to the effects of nighttime and perhaps, dream time. The usual interpretations of familiar Kharkiv spots are rejected as inadequate. The Uspenska Bell Tower, the Bursatsky Slope, the bread-baking plant at the Gorbaty Bridge, become semi-visionary landscapes. The infrared effects that discover and explore the heat-life of nature, form a quasi-psychical matter which appears deceptively real. All this seems to be taking place in some strange location, rather than the old familiar city of Kharkiv.

. 2000.jpg)

©.Eugeny Pavlov. Detonation of hippy-end (with the musical performance by Andrey Bogatyriov Magic Violin). 2000

In 2000, The Violin by Pavlov was showed in nearly full volume (70 prints) in the art gallery at the Kharkiv Opera and Ballet Theatre. The exhibition was titled The Detonation of Hippy-end. Despite thirty years distance in time, the power of non-conformism conserved in these prints broke free. This unused footage of a 1970s underground performance with Kharkiv hippies sounded very up-to-date along with the Magic Violin musical performance by Andrey Bogatyriov. Contemporary interest in the hippie movement, with their quasi-aesthetic gestures (nudity being one of those) brought attention to this action from young audiences. The flower-kids used this ritual ‘flower-language’ of nudity as a very powerful sign of disarmament, exposure, and unveiling.

©.Boris Mikhailov. The Blue Series.1993

The title of one of Sergei Bratkov’s key works is No Heaven (also translated as “No Paradise,1995). Regardless of the negative particle, it points to the focus of humanitarian culture, centered on a search for happiness. The series of photos made in an orphanage (Artificial Breath), his Children series, remind us of the popular adage “children are the flowers of life.” The Frozen Landscapes photo-performance, dedicated to frozen-to-death homeless people (“snowdrops” in the local vernacular), completed the sad perspective of Ukrainian flower-kids.

. 2013.jpg)

Case History, or Homeless (1997–1999) © by B.Mikhailov in Yermilov Centre (Kharkiv). 2013

This global subject matter also nurtured Boris Mikhailov’s By the Ground (1991), At Dusk (1993), and Case History (1997–1999), unique in Kharkiv photography for their depictions of the 1990s Ukraine. By the Ground shows narrow side-streets with gaping black doorways, dark blind windows of houses, walls with peeling plaster, barrels, bags of cement, wheelbarrows, smoking trash cans, wheel ruts, dirty bare feet, unevenly paved roadways, and other debris. The desolate streets are choked by a heavy gray fog creeping over the pavements like poison gas, but in fact it is the blue firmament coming down to earth (At Dusk). The abandoned city looks dismal, dark, and frozen. By referencing vague concepts, with their system of hedges as “deviations from determinism,” the artist makes his viewers anxious and uncomfortable.

© E.Pavlov and V.Shaposhnikov. Fragments from The Second Heaven. 2003

1999 saw the beginning of a project (finished in 2003) for which the ceiling of the Sistine Chapel became its means of identification – the instrument of its deciphering. It was The Second Heaven by Eugeny Pavlov and Vladimir Shaposhnikov (curator Tatiana Pavlova), created in order to be exhibited on a ceiling in the genre of monumental photography, thus breaking the law described by the immortal slogan of the Soviet epoch: "monumental, not momentary."

in Kharkiv Municipal gallery. 2003.jpg) Here, the gravitational shift attained by an unusual exhibiting location becomes the principal means of seeing and reading one’s own heaven, as an attempt at spatial embodiment of the typology of contemporary historicism. The canopy of heaven is the ideal place for such a critical analysis of history. The canopy, or vault, itself is an unlimited addition of spaces and dimensions, the lack of which is sometimes felt so acutely by photography. The second discovery of photography in our days – as the technique corresponding most of all with the essence of what had been the first act of creation – the separation of light from darkness – is asserting the genuineness of its purpose. The projectional character of "drawing by means of light," or taking a picture with the help of photography, makes it free and easy for us to transfer the "earth" to the "heaven above."

Here, the gravitational shift attained by an unusual exhibiting location becomes the principal means of seeing and reading one’s own heaven, as an attempt at spatial embodiment of the typology of contemporary historicism. The canopy of heaven is the ideal place for such a critical analysis of history. The canopy, or vault, itself is an unlimited addition of spaces and dimensions, the lack of which is sometimes felt so acutely by photography. The second discovery of photography in our days – as the technique corresponding most of all with the essence of what had been the first act of creation – the separation of light from darkness – is asserting the genuineness of its purpose. The projectional character of "drawing by means of light," or taking a picture with the help of photography, makes it free and easy for us to transfer the "earth" to the "heaven above."

The photo-panels are framed by figures of pageantry, which in the Italian school of painting in the Renaissance epoch were called "slaves." Historians argue that the concept of a "slave" had appeared in ancient Rome even before slavery as an institution was introduced there. This name was given to a human creature which had lost its independent status, almost even his right to live, and therefore was classified with those already dead, with a rather slight chance to be included in the number of those who were really alive (to these belonged prisoners of war, sentenced criminals, etc.). These faceless robots, this "cannon fodder" of history, whom many people in Ukraine saw not so much as post-Soviet, but rather as neo-Soviet creatures, became part of the project. The long line of these figures became a symbol of the times changing, many generations following one another.

The viewer of The Second Heaven project becomes aware of the fact that its initial elaboration had been carried out beyond the traditional functions of photography, utilizing the active capital which it gained during the recent decades in the so-called "social plastic art." The great amount of the material used in the project and the degree of its generalizations covered by the common roof of Cortasar's architectural fantasies, have changed The Second Heaven into a really monumental project. However, no appropriate setting could be found in Kharkiv, and the photographic epic was not displayed on a ceiling. Instead, the interior of the small Municipal Gallery was fully plastered with the photographs when this project was exhibited there in 2004.

(Above image: Y.Pavlov and V.Shaposhnikov.The Second Heaven (curator T.Pavlova) in Kharkiv Municipal gallery. 2003)

(image right: The Museum of Photography in Kharkiv (curator T.Pavlova in the center). 2001)

The wrap-up of “Soviet History” coincided with the century’s and the millennium’s end. The time had come for a critical re-evaluation of Kharkiv photography, to which end an important venture – the Museum of Photography in Kharkiv – was launched. I was the one who initially proposed the idea. The city authorities were not interested, but the project was launched, nevertheless. Its first event was an exhibition (2001) that gave the viewers a taste of the great collection and also displayed works by a number of Polish and American photographers.

© Roman Pyatkovka. Soviet Photo.2012

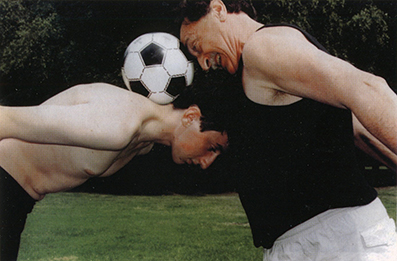

The anthology of Soviet reality compiled by the Kharkiv School of Photography is complemented by Roman Pyatkovka’s (The Games of Libido, 1995; Propaganda Poster, 2012) and Pavlov’s (Home Life Book, 2002) projects which featured pictures from the Soviet archive. In the 2000s, the books Yesterday’s Sandwich and Suzy and Others by Boris Mikhailov,  containing pictures taken in the 1960s and 1970s, were published and simultaneously shown as gallery exhibitions. During this period, his work with the archives led the artist to a re-evaluation of past experience. Mikhailov’s 2003 series, Football, where autobiographical family scenes are used to ridicule the romantic notion of love, serves as an ironic footnote to the early period in Kharkiv photography – the last in a long list of sentimental affections abandoned by the artist at a more mature stage of his creative career.

containing pictures taken in the 1960s and 1970s, were published and simultaneously shown as gallery exhibitions. During this period, his work with the archives led the artist to a re-evaluation of past experience. Mikhailov’s 2003 series, Football, where autobiographical family scenes are used to ridicule the romantic notion of love, serves as an ironic footnote to the early period in Kharkiv photography – the last in a long list of sentimental affections abandoned by the artist at a more mature stage of his creative career.

No doubt this was the result of, among other things, Mikhailov’s “stardom,” after the 2000s saw him receive the prestigious awards from Hasselblad (Gothenburg, Sweden, 2000), CityBank (UK, 2001), and Kaiserring von Goslar (Germany, 2015). Mikhailov’s work has been exhibited in New York, London, Paris, Tokyo, Berlin, and other major cultural centers of the world. One of the highest points in his career was Mikhailov’s participation in the 2007 Venice Biennale as a representative of Ukraine (The Poem of the Inner Sea). Furthermore, Mikhailov was the first photographer since Rodchenko’s time to have his works purchased by the famous Museum of Modern Art in New York. (Above image: © B.Mikhailov. Football. 2003)

During the late 1990s and the early 2000s Kharkiv’s photographic scene centered around the Palitra private gallery, founded by Andrei Avdeyenko and Sergei Vasilenko, and located at the eponymous photo studio. From the outset, the gallery dealt primarily with photographic exhibitions and performances; over forty exhibitions took place there. But this small (only 20 square meters) gallery also hosted the exhibition “Unofficial Russian Art of the 1960s” (May 6-27, 1999), which was brought from the United States by A. Glezer and featured works by celebrated nonconformists, such as Oskar Rabin, V. Sitnikov, L. Masterkova, Nikolai Vechtomov, V. Yankilevsky, and others. At the time, photographic exhibitions in Kharkiv were also held at the Municipal Gallery (curated by T. Tumasyan), the Academia Gallery (curated by T. Pavlova), and the ArtHouse Gallery (curated by I. Manko). The final recognition of Kharkiv photography came when it was exhibited by the Kharkiv Fine Art Museum and the House of Artists.

. 1990s.jpg)

Exhibition in Palitra Gallery (curator A.Avdeenko). 1990s

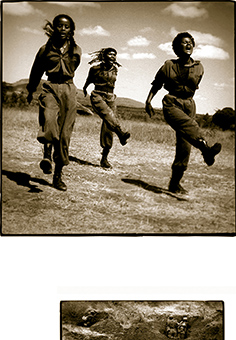

© Guennadi Maslov. Halves Series. 2002

Some photographers, who left Kharkiv in the 1990s, started to return to the city’s cultural landscape in the 2000s. For example, after a long absence, Guennadi Maslov’s work re-entered the Kharkiv art scene (his Halves series, 2002). The works were based on the newly interpreted material from the United States (the author moved to Cincinnati, Ohio in 1993, where he currently lives), Ukraine, and Ethiopia. The images were marked by nostalgia and differed radically from his earlier works, created in the direct photography paradigm of the Gosprom Group aesthetics. The brutality and abruptness of the 1980s, a hallmark of the provocativeness of social reportage of that time, were gone. They were replaced by the retro lyricism of the digital gesture, by the reflective escape, by the special square cropping. The technique was applied to the images produced with both medium and 35-mm cameras. In this way, the dynamic compositions, typically produced with the small format equipment, evolved into the essentially static ones characteristic of the medium format. But the main concept of the works was in their social dimension, seen as a search for compromise uniting conflicting notions and polar cultures. Maslov says, half in jest, "My works are a reconciliation, an attempt to reconcile the Western and Eastern halves of my brain.” 4

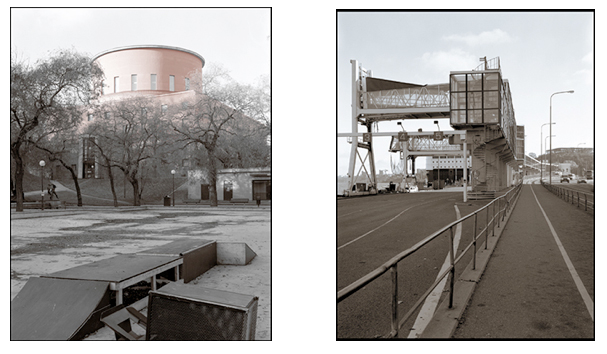

©. Misha Pedan. Monument.2003

Another Gosprom group artist, Misha Pedan, also contributed to connecting Kharkiv with the outside world. In 2003, he exhibited his Monument project at the Academia Art Gallery. The essence of that exhibition is a conceptual landscape of Stockholm. Photographing with a 4x5 camera format assumes a meticulous search for an object to photograph. The images depicting city environment were selected by the criterion of a viewer’s emotional “turn-on,” on the contextual effect rather than form and shape. The exhibition is an acme point allowing an artist to understand many things. Thus, for instance, it became obvious that, presenting a conceptual series of Stockholm landscapes, Misha Pedan still represented the Kharkіv School of Photography and the “grey city” of Kharkiv itself.

Both Maslov and Pedan were a big influence within the Kharkiv photography scene. Beside attracting a wider audience of viewers and admirers, each of them made contacts with the outside world. Maslov arranged a number of Kharkiv photo exhibitions in the United States. An exhibition of works by M. Chernov, I. Manko, and A. Avdeyenko took place in the winter and spring of 2015, offering multilevel reflections on the recent events in Ukraine.

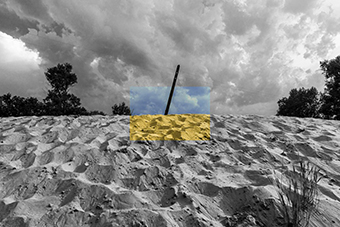

© Igor Manko. The Golden Ratio of Ukrainian Landscape. 2014

Having established a foothold in the cultural scene of Stockholm, Pedan set himself to bridging the gap between Ukraine and Sweden, especially in the field of photography. Among his successful endeavors was the creation, with R. Pyatkovka, of the Ukrainian Photographic Alternative, an alliance dedicated to promoting alternative approaches in contemporary photography.

The threatening dynamics of the involution of man, represented in Kharkiv photography at the turn of the 21st century, shows the depth of psychosomatic crisis. The antropocreation experiment, the revolution of spirit, the cosmic crusade - all these great projects threatened to surrender a human body into the domain of flora instead of attaining Paradise. This is the futurologist prognosis of the artistic actions this essay has considered. A local problem of the contemporary Ukrainian society, namely the search for a strong hero, is also reflected in this art discourse. The conflict between “vita heroica” and “vita minima” has remained an ongoing problem of Ukraine’s culture over many centuries and has reached extraordinary incandescence today.

The new generation of Kharkiv photographers that emerged over the last decade received extraordinary motivation for the heroic theme (the current war), galvanizing the Kharkiv School of photography discourse and thus constitutionalizing it. At the same time, it ceased to be a solely local phenomenon, earning a distinct status as an art form.

. O.Burjak, T.Pavlova, V.Pedan.jpg)

Exhibition Monument by Misha Pedan.2003 (curator T.Pavlova, Academia Gallery).

O.Burjak, T.Pavlova, V.Pedan © T.Pavlova

1.Interartscape – term, which appeared in the course of the project. See: Pavlova T. In the interval of Interartscape in Imago, 1996 / 97, № 3, p.73.

2. Zimmer W. Ukrainian Photos, Rich and Raw in The New York Times, July, 23, 1995.

3. Pavlova T. In the interval of Interartscape in Imago, 1996 / 97 (Winter), № 3, p.73.

4. Maslov G. Artist’s statement in Month of Photography (Catalogue) / Central European House of Photography, Bratislava, 2002, P. 102.

© Tatiana Pavlova, 2015

We welcome your comments. VASA Exhibitions are the result of various curators, artist, and photographers.